Ode to a Black Female Aviation Pioneer

Gloucester County Historical Society Performance Celebrates Bessie Coleman

As she arranged the props for her performance in the Gloucester County Historical Society Museum, historical interpreter Daisy Nelson-Century set up a cluster of spindly cotton bush branches. Then, pulling out handfuls of cotton balls from a tattered bag, she glommed the white puffs onto the bush, creating the symbolic Southern sharecropper fields where the subject of her performance — Black aviation pioneer Bessie Coleman — began her extraordinary life in the last decade of the 19th century.

As usual with the former Philadelphia school science teacher turned theatrical re-enactor, Nelson-Century also laid out several different sets of clothing that she would rapidly change into as she walked the audience through the 34 years of Coleman’s high-flying life.

Bent over the cotton bushes in her raggedly bib overalls and ratty straw hat, Nelson-Century in the persona of Coleman noted out loud that she saw a ladybug on the cotton bush and proclaimed out loud in the voice an excited young girl, “If I had wings like that ladybug, I’d fly far away from this field and wave to everyone down below as I did it!”

And the incredible part of Coleman’s story is that 18 years later, she did that very thing in real life — and as an international celebrity.

Race and Gender Barriers

The biographic tale Century performed during the next 90 minutes was both that of the early heady days of seat-of-the-pants aviation and one of its most unique figures who overcame daunting racial and gender barriers to rise by grit and gumption to become a beloved icon of the African American community across the country.

Even as an elementary school student forced to spend half of each semester picking cotton on the family farm, Bessie Coleman stood out for her keen intellect and affinity for mathematics. Despite the segregated and impoverished conditions in which she lived, she excelled academically and, at 18, was accepted into Oklahoma Colored Agricultural Normal University, which was a Historically Black College and University (HBCU). But her money ran out after her freshman year, and she joined the great African American migration north to Chicago to live with her two brothers, Walter and John. Both had recently returned from serving in the 370th Regiment of the Illinois National Guard in battles across France during World War I.

Coleman went to Burnham School of Beauty Culture in Chicago and found work as a manicurist in a men’s barber shop in the heavily African American community of Chicago’s South Side. Her brothers regaled her with colorful stories of the airplanes and pilots that were an exciting new aspect of military operations around them during the War. And one of them teased her about her low-pay manicurist job, pointing out that in other countries, like France, that were not segregated, women were able to get good paying jobs, including even as airplane pilots.

Rejected by U.S. Flight Schools

The idea of flying took firm root in Coleman’s imagination. She applied to three different American flying schools. But all of them rejected her because they did not admit women or Black people.

In 2024, the idea of being able to fly through the sky is as commonplace and pedestrian a thing as flipping on the electric lights on in your home or jumping into your car for a hundred-mile turnpike drive. But a hundred years ago, the idea that human beings had constructed metal machines that could take off and fly for hundreds of miles at 3,000 feet above the ground was awesome to the point of near disbelief. And the people who flew these wonder machines were perceived as some the bravest and most talented heroes of the day.

Bessie Coleman was determined to become one of them.

She could not get it out of her mind that women were accepted to flying school in France and were becoming pilots. That knowledge took over her life. She began studying French. She mailed off her application to that country’s most famous flying school — the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy. And when she was ultimately accepted, her joy of that was tempered by a frantic search for the money needed to fund her journey, living expenses, and schooling in France. Beyond her saved money, she sought donations from friends, neighbors, and various local Chicago African American organizations.

One of the responders to her funding appeal was Robert S. Abbott, publisher of the Chicago Defender newspaper, one of the country’s most important and powerful African American media companies. He encouraged and supported Coleman at the same time he connected her to the business executives, newsrooms, and top-level entertainment personalities of elite Black society — all of whom bought into Coleman’s quixotic quest to be the first Black female to become a licensed airplane pilot.

Steamship Ticket to France

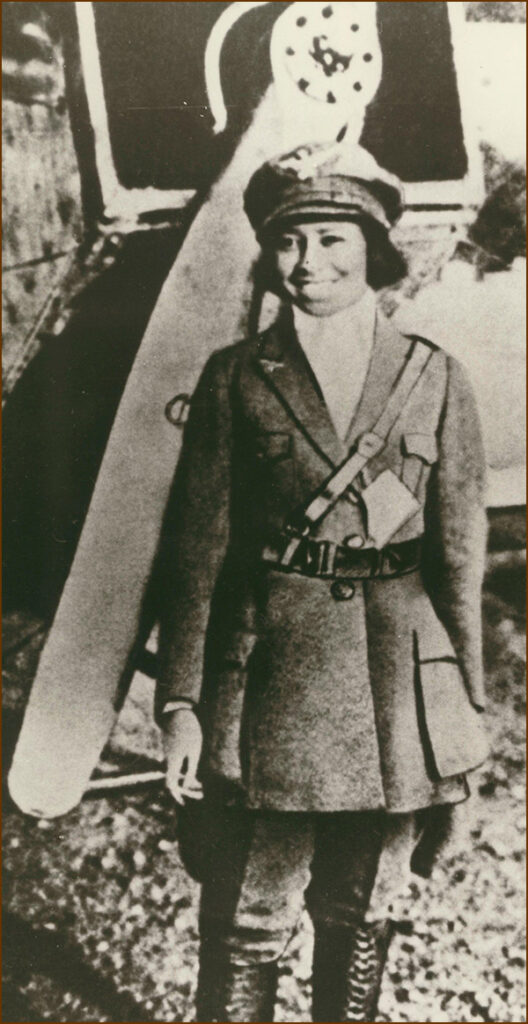

Coleman bought her steamship ticket, arrived at the Caudron Brothers’ school, began her flying education, and seven months later in 1921, received her international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI).

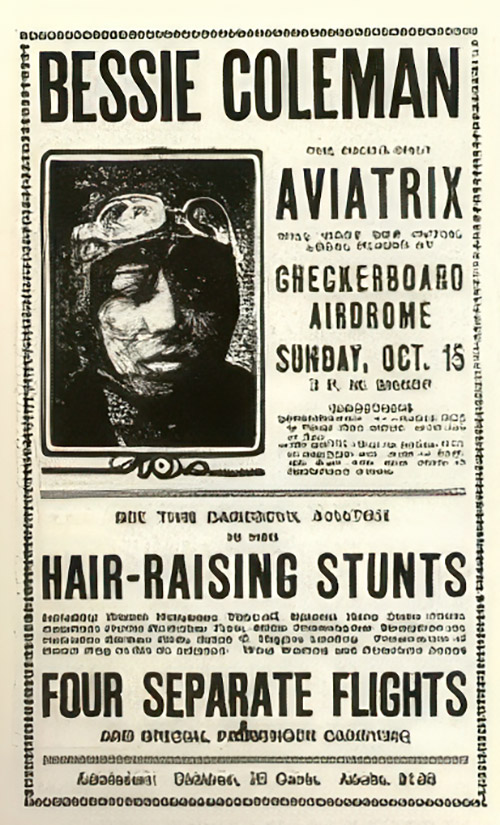

Seven months later, she returned to France and Caudron Brothers’ for the advanced training that enabled her to fly a plane in loop-the-loops, barrel rolls, spiral dives, and other dangerous maneuvers. Back in the states, Coleman, flying her Curtiss JN-4 biplane, wowed large barnstorming air show audiences and the press with her airborne stuntsmanship and derring-do. Occasionally she elicited communal gasps as she or her passenger parachuted from the plane, floating down to land in front of the crowd below.

Although her flying career lasted only five years, it made her a national celebrity and role model among African Americans across the country. She was closely affiliated with African American organizations that promoted her shows. For instance, the national Negro Welfare League arranged speaking engagements for her in Black churches and theaters as she traveled.

Civil Rights Advocacy

Coleman used her celebrity to advance the Civil Rights struggle — and her advocacy was not subtle. At some of the air shows, particularly in the South, there were separate entrances for whites and Blacks. Under threat of not performing, Coleman demanded there be a single entrance for everybody — and won that concession from event promoters.

In 1926, the day before an air show sponsored by the Negro Welfare League at the Paxon Field in Jacksonville, Fla., Coleman was flying in the passenger seat as her mechanic and associate William D. Wills piloted the plane. Thousands of feet in the air, she unbuckled her seat harness so that she could look over the side of the plane to scour the terrain below to identify the best spot for a parachute landing in the next day’s show. But a wrench in in the cockpit slipped into the Wills’ controls, jamming them and sending the plane into a tailspin. Unharnessed, Coleman fell out of the plane, plummeting to her death. The plane crashed a short distance after that, killing Wills as well.

Flying School for African Americans

At the time of her death, Coleman was saving money and planning to open America’s only flying school for African Americans. In a 1929 in tribute to her, African American pioneering aviator and businessman William J. Powell founded the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in Los Angeles. It was an aviation association and training facility for African American pilots, mechanics and technicians.

As she ended her Historical Society Coleman performance, Nelson-Century noted that she changes the ending of the story depending on whether there are children in the audience or not. “A few years ago, I was doing Bessie Coleman in an elementary school for fourth and fifth graders,” she explained. “And when I got to the part where Coleman suddenly dies at the height of her career, they all started crying, so now I only include the dying part for adult audiences.”