Rare Book Find Sheds Light on Gloucester County’s Whiskey-Making Past

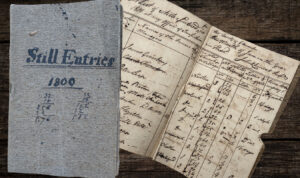

County Commissioners Transfer Two-Century-Old Ledger to Gloucester County Historical Society

Although it’s not a thread of local history that’s much written about or celebrated, the making of whiskey played an inordinately large role in American colonial life. The Gloucester County Commissioners and County Clerk recently came across and acquired a rare 224-year-old book that sheds further light on home distilling around the county. Titled “Still Entries 1800,” the hand-written ledger documents locations, gallons of whiskey produced, and taxes paid by whiskey still operators in the townships that made up old Gloucester County — Newton, Woolwich, Greenwich, and Deptford.

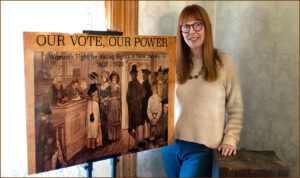

In a late September ceremony in the Gloucester County Records Room, the County Commissioners transferred possession of the rare ledger to the Gloucester County Historical Society as part of their long-standing agreement recognizing the Society as the official repository of important historical records that don’t directly relate to official county government operations.

“This still ledger is not technically a county record,” said Gloucester County Records Manager Michell Everly. “It’s a federal record that comes from the era of the 1791 excise whiskey tax. But it’s a natural part of the county record in the way it documents the activities of specific county residents.”

Vivid Local History

President of the Gloucester County Historical Society Don Kwasnicki thanked the Commissioners, Clerk, and Records Room staff. “We greatly appreciate being entrusted with this very rare work that provides information from an important historical era that many people don’t know much about. The fact that it names the individuals who were operating stills throughout the county brings the historical story of the Whiskey Rebellion home in a very vivid way.”

Even as they began arriving on the east coast in the 1600s, European colonists were using stills and local grains, vegetables and fruits to manufacture alcoholic beverages that were a daily staple of their families’ lives. They consumed alcohol at nearly every meal and, on average, drank three times more alcoholic beverages than modern day Americans. Home brewing was a routine, widespread activity with the sale of copper whiskey stills with capacities ranging from ten to 1,800 gallons being a common element of newspaper advertising and local commerce.

Many famers used surplus grain to produce large quantities of whiskey that they sold or used as currency to purchase other needed goods. For many farmers, the practice generated a crucial stream of annual revenue their farms needed to remain financially viable. For instance, the records of George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate include a whiskey distillery that produced 12,000 gallons a year.

The Whiskey Rebellion

But the nature of home-based whiskey production changed dramatically as the country came out of the Revolution and created a new federal government needing to find ways to fund itself and repay the enormous debt it incurred while waging war against the British. In 1791, the new Congress established a federal tax system targeting luxury goods like carriages and snuff, along with slaves, land holdings, and — most controversial of all — domestically produced whiskey. Local federal agents across the states were tasked with identifying, visiting, and documenting the details of local still production. They recorded the still capacity and gallons of whiskey produced to calculate and collect those families’ whiskey tax bills.

In heavily farmed regions of western Pennsylvania, the local opposition to the Whiskey tax became a major, violent cause. Organized farmer militia bands attacked the homes of local tax inspectors. Others took the tax collectors who came to their farm prisoner, often tarring and feathering them before running them off. By 1794, this anti-tax mob violence had become so bad that President George Washington himself led 13,000 federal troops into the Pennsylvania farming districts to suppress the rebellion.

John Clement of Haddonfield

In Gloucester County, one of those tax agents was John Clement of Haddonfield, a town located in what was then the northern section of Gloucester County. Clement, a prominent citizen, judge, and historian appointed to the Office of Inspection, was charged with collecting whiskey information and tax payments throughout the county.

In his 1800 ledger that is now with the County Historical Society, Clement documented the many prominent businessmen and politicians who were operating their own stills. These included Joseph Cooper, Charles French, James Graisberry, and the Philadelphia company Wood & Gill. Cooper was a member of the influential Quaker family best known for their role in founding Cooper’s Ferry, which later became Camden, New Jersey. French was a Quaker landowner and justice of the peace who was heavily involved in civic religious, and economic affairs around Gloucester County. Graisberry was a printer and local politician who held various official positions in Gloucester County. Wood & Gill, a major woodworking firm producing high-end furniture and clocks, appears to have operated a Gloucester County still house as an adjunct to its major business.

In 1802, the highly unpopular whiskey tax was repealed by the new administration of President Thomas Jefferson. Although the rebellion of 1794 had been suppressed, the tax remained a point of widespread political discontent. At the same time, the Jefferson administration determined that the cost of enforcing the whiskey tax had become greater than the revenue it generated, particularly because of widespread evasion.